Accessibility to Land Administration by Grassroots

Stakeholders in Vietnam: Case study of Vinh Long Province

Mau Duc NGO, Vietnam; David MITCHELL, Australia;

Donald GRANT, Australia;

and Nicholas CHRISMAN, USA

1)

This peer reviewed paper was presented at the FIG Working Week 2016 in

Christchurch, New Zealand. The article presents the evaluation of

grassroots stakeholders’ accessibility to the land administration, and

to the development of a modern land administration system in Vietnam.

Key words: access to land;

e-governance; land management; land stakeholder perception; land

administration; Vietnam

SUMMARY

The trend in modern land administration systems towards e-land

administration aims at improving access to land information and services

for all stakeholders. Vietnam is no exception in this trend. The

government has made large investments to develop the land information

and registration system with the strong support from donor-funded land

registration projects. One aim of land registration and titling is to

build a transparent land administration system. Most investments have

focused on the development of a computerised system to improve land

administration delivery services. However, there have been some

technical and non-technical factors which have become barriers to the

implementation of an effective land administration system in the

country. This paper presents the evaluation of grassroots stakeholders’

accessibility to the land administration, and to the development of a

modern land administration system in Vietnam. This research is based on

a case study which investigates the challenges for development of a

conceptual spatial data infrastructure to increase access to land

information by all stakeholders in Vietnam.

In Vietnamese:

Xu hướng hình thành hệ thống quản lý đất đai hiện đại tiến tới hệ

thống quản lý đất đai điện tử cải thiện sự tiếp cận thông tin và các

dịch vụ đất đai cho tất cả các đối tượng có liên quan. Việt Nam không

nằm ngoài xu hướng này. Trong thời gian vừa qua, Chính phủ Việt Nam đã

đầu tư một lượng kinh phí lớn trong lĩnh vực đất đai với sự hỗ trợ mạnh

mẽ từ các dự án tài trợ. Mục tiêu của công tác đăng ký đất đai và cấp

giấy chứng nhận quyền sử dụng đất là tiến tới xây dựng một hệ thống quản

lý đất đai minh bạch. Hầu hết các dự án đầu tư đã tập trung vào việc

phát triển một hệ thống thông tin đất đai để dần cải thiện dịch vụ quản

lý đất đai. Mặc dù vậy, có một số hạn chế cả kỹ thuật và phi kỹ thuật đã

cản trở việc thực hiện một hệ thống quản lý đất đai có hiệu quả trên cả

nước. Bài báo này trình bày kết quả khảo sát việc tiếp cận thông tin và

các dịch vụ đất đai của người dân ở cấp cơ sở và đánh giá sự phát triển

của một hệ thống quản lý đất đai hiện đại ở Việt Nam. Nghiên cứu này

được thực hiện trên một địa bàn cụ thể, khảo sát những khó khăn, thách

thức trong việc phát triển một cơ sở hạ tầng dữ liệu không gian để tăng

cường tiếp cận thông tin đất của tất cả các bên liên quan ở Việt Nam.

1. INTRODUCTION

Land and geographic information underpins many of the objectives and

strategic goals of governments, including natural resource management,

environment monitoring, land-use control, climate change adaption, and

disaster risk management, as well as socio-economic development. Spatial

and non-spatial information about land are important for government in

land management and administration decision-making, but also for

landholders in making decisions about their land. The role of spatial

information to support decision making of local, national, regional and

global issues was recognised more than two decades ago at the Rio Summit

(1992), and is still central to discussions about the Sustainable

Development Goals. Land information has often been described as an

element which presents the location of resources and helps people to

understand the relationships between real objects and resources. This

concept enables the visualisation of resources’ locations to support

planning and management. Land administration assists in the protection

of scarce community resources by allocation of the rights to them,

creation of restrictions on them; and establishment of responsibilities

of related stakeholders. The utilisation of spatial data and services

allows decisions to be made about optimising the use of land and becomes

one of the key principles for sustainable management and development

(Muggenhuber, 2003; Steudler & Rajabifard, 2012).

Furthermore, the security of land use rights (land tenure), together

with information about access to land, has been identified as important

for the reduction of poverty (FAO, 2012; Maxwell & Wiebe, 1999; Quizon,

2013; Widman, 2014) and meeting the broader sustainable development

goals objectives. The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance

of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food

Security (FAO, 2012) calls on States to recognise, record, and respect

all legitimate rights to land. The way that land rights may be recorded

is in the formal land administration system. However, it is often stated

that approximately 70% of all land rights globally are not recorded in

the formal land administration system.

In Vietnam, information on property rights, including land use rights

and related land information, has recently been recognised as an

important competitive indicator to attracting investors at the

provincial and municipal level (Malesky et al., 2015). According to Thu

and Perera (2011), access to land is a sensitive issue that may hinder

foreign and private investments, as the stability of land use is a

factor that multi-national enterprises consider when investing in

Vietnam.

Stakeholder understanding of, and participation in, land

administration process is an important element in land administration

delivery and the provision ofland-related services. A transparent land

administration system requires active participation by individuals,

households and organisations to increase access to land informaiton. As

the largest user, grassroots stakeholder’s understanding and

participation are critical when assessing the development,

implementation, and maintaince of land administration.

Since the late 1990s, the Government of Vietnam has made large

investments to develop a modern land administration system including

land registration and the issuance of Land Use Right Certificates

(LURCs) with the strong support from international donors such as

Australia, Sweden, ABD, and The World Bank Group (World Bank, 2010).

Such a modern transparent system will contribute a good governance and

strengthen the trust of local people in land services and activities.

The institutional arrangements have been improved by separating the

state administration organisations and public service provision units,

together with the establishment of a unified and decentralised system of

land administration at all levels over the last decade (Vietnam National

Assembly, 2003; World Bank, 2009). However, there has been a

considerable gap between the land policy and its practical

implementation to ensure the access to land by stakeholders. For

instance, the standard requirements for land registration offices have

not yet been developed and applied, while the procedures for the land

titling process have retained complexity which may encourage corruption

in the land sector (Embassy of Denmark, Embassy of Sweden, & World Bank,

2011).

There has been an estimated $60 million of investments per year for

cadastral survey and mapping, including procurement of surveying

equipment and technical services (World Bank, 2011). However, several

reviews have reported limitations in the land sector in Vietnam,

especially in term of ensuring and increasing efficient access to land

information by stakeholders. As a consequence, over the last few years

the land sector in Vietnam has been rated in the top three sectors for

corruption (DEPOCEN, World Bank, UKAID, & VTP, 2014; Martini, 2012;

World Bank, 2010; World Bank & Government Inspectorate of Vietnam,

2013). There have been both technical and non-technical issues that have

caused problems. In particular, land administration related services and

activities, and accessibility to land information for land users, needs

further development.

This paper presents the results of one element of a PhD research

project being undertaken to develop a conceptual spatial data

infrastructure model for land administration system (SDI Land) in

Vietnam with a case study of Vinh Long Province (hereinafter called Vinh

Long). The model aims to increase access to land information by all

stakeholders. This paper considers the information needs of one group of

these stakeholders - those at grassroots level.

This research employed a multi-method setting using a case study

strategy that includes both quantitative and qualitative methods. The

qualitative methods involved interviews of related stakeholders,

including managerial officials, policy makers at the central ministries,

and technical and managerial staff at provincial level, international

organisations, donors, private and academia sector as well as community

members through personal interviews and focus group discussions. The

quantitative methods included questionnaires about people’s attitudes,

thoughts, and evaluations of engaging with land registration services at

the government agencies; the difficulties encountered, and deficiencies

and expectations in accessing land information.

The grassroots stakeholder consultation was conducted in Vietnam in

late 2013. Three focus group discussion meetings and 160 individual and

household questionnaire survey were conducted in Vinh Long. The

selection of participants was made randomly by third parties to ensure

the nature of collected data and the voluntary participations. However,

there was a balance in both gender and cultural background for the

participants of focus group discussions and questionnaires at the

grassroots level. As the research involved human participants, the

ethical issues were considered and approved to conform to the Australian

National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research before the

fieldwork conduction. The data collection was in Vietnamese language and

was then analysed by computer-aid data analysis software packages,

including MS. Excel and QSR NVivo.

2. VIETNAM LAND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Land Tenure in Vietnam

In Vietnam, land belongs to whole population, managed by the State

and while private ownership of land is not recognised, land use rights

can be issued (Vietnam National Assembly, 2013a). The State recognises

and protects the land use rights of land users (Vietnam National

Assembly, 2013b). In this context, as a special property, the meaning of

the term land use right in Vietnam is not significantly different to the

meaning of land ownership. In other words, it is the most secure form of

tenure for landholders in Vietnam. In certain areas LURCs are allocated

to individuals, households, organisations, and communities (hereinafter

called land users) to use stably. No LURCs are issued for land on which

land use rights have not been allocated, and this land remains under the

control of the State.

LURCs are essentially usufruct rights, meaning that the land users

may use land, but cannot own the land. Land use rights entitle land

users to exchange, transfer, inherit, mortgage, lease, sub-lease,

bequeath and donate land use rights, guarantee and contribute capital

using land use rights (Vietnam National Assembly, 2003).

According to data from the General Department of Land Administration

(GDLA), as of 2013, about 90% of agricultural land area, 75% of urban

residential land area, 90% of rural residential land area, and 70% of

forestland area had been issued LURCs. However, cadastral records,

including cadastral maps, are largely incomplete, inaccurate, and

out-of-date; and thus cannot support the needs of land related services

delivery. By the end of 2014, there has been only about 20% of LURCs

issued with the names of both spouses as promoted and regulated by land

laws and policies. The system itself is cumbersome and inefficient,

lacks transparency, and has not yet provided the end-users with quality

services. As a result, it is difficult and costly to conduct land

transactions or to use LURCs for mortgaging to access to credits.

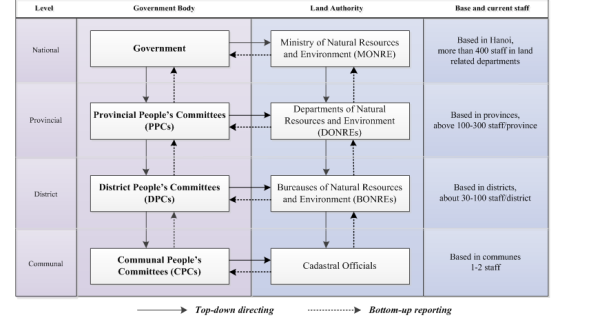

2.2 Vietnam’s Decentralised Land Administration System

Vietnam’s land policies are administered through a hierarchy of

authorities at the central level, sixty-three provinces and cities, more

than seven hundred districts and over ten thousand communal

administrative units (including communes, wards and towns). The Vietnam

land administration system is a multi-level and decentralised system.

In 2009, GDLA was re-established under the Ministry of Natural

Resources and Environment (MONRE) and has become the primary central

level body in the country for land administration activities. GDLA is

responsible for advocating with the other government agencies for

necessary laws to reform public land, land registration and other land

regulations for more efficient resource management system in the

country. The activities of GDLA focus on state administration of land,

directing and organising inspections of land nationwide and directing

the surveying, measurement, drawing and management of cadastral maps,

land use status maps and land use planning maps nationwide. GDLA is

based in Hanoi.

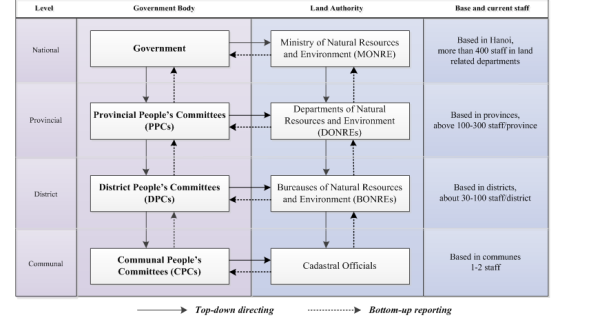

Figure 1: Vietnam Decentralised Land

Administration System

At the provincial and district levels, the natural resources

departments as well as the Commune People’s Committees, supported by

cadastral officials are responsible for land management within the

administrative boundaries. Respectively, the upper level authorities

provide guidelines to lower ones. Staff and organisations belong to

respective people’s committees at the same level (Figure 1). Most of the

land administration activities happen at the local levels.

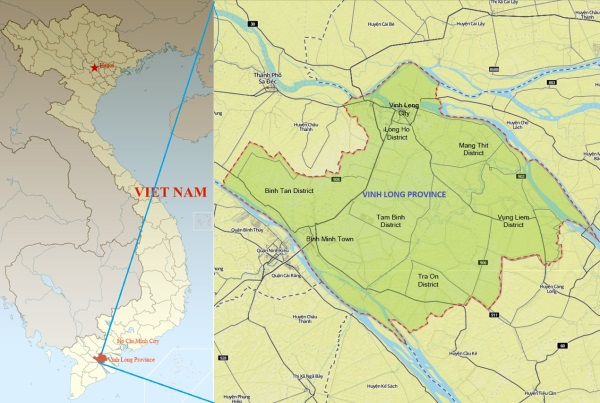

3. VINH LONG CASE STUDY

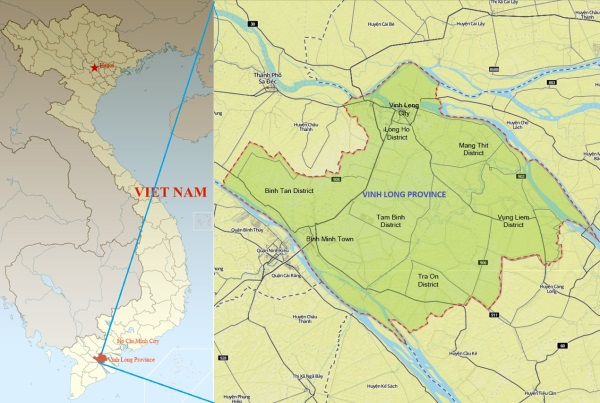

3.1 Land Tenure Profile in Vinh Long

Located in the Mekong Delta region, lying between two major rivers in

the area (Figure 2), Vinh Long plays an important role for agricultural

production and is well known for fishing in the south of Vietnam. Like

other traditional agricultural provinces, land is important to people

for both residential and farming purposes. Vinh Long is the smallest

province covering an area of approximately 1,500 km2 and has a

population of 1.04 million (http://www.vinhlong.gov.vn/Default.aspx?tabid=1255

accessed on August 21, 2015) over approximately 265,000 households with a

density of 700 people /km2. The Province is subdivided into eight

district-level administrative units including six districts, a

district-level town, and a city; 109 communal-level administrative

units, including 94 communes, 5 communal-level towns, and 10 wards.

Figure 2: Vietnam and Vinh Long Province in the south of Vietnam

(non-scale maps; extracted from www.vietbando.vn)

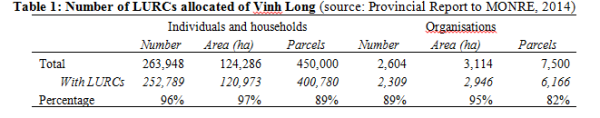

Vinh Long was one of nine provinces covered by a World Bank funded

project (VLAP) implemented during 2009-2013, and extended and closed by

end of 2015. The Province was considered as a lead province in the

project implementation with good progress, strong commitments of

provincial leadership, and the active participation of land users during

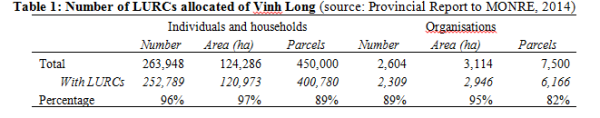

the project implementation. The figure of land tenure in the Province as

of 2014 is presented in Table 1.

The land administration system of Vinh Long is similar to the other

provinces with the DONRE belonging to PPC and nine BONREs at district

level. At the provincial and district levels there are land registration

offices organised to deal with all land administration activities

related to grassroots stakeholders. Cadastral officials at communal

level assist with the CPCs and BONREs land management related

activities.

3.2 Selection of Case Study Districts

Three communal administrative units were selected including Ward 2 of

Vinh Long City, Trung Thanh Tay and Trung Hiep communes of Vung Liem

District to represent for all three urban, peri-urban and rural

communities.

The selection was based on number of criteria including technical,

professional and organsational development as well as academia

collaboration of the provincial leaders in the land sector.

Demographical distribution and geographical range were also taken into

consideration of the case study areas. Other criteria included the

availability of as many land services as possible, the commitment of

provincial leaders and the accessibility of investigators. Land tenure

profiles of the three communes were similar to the whole province as

shown in Table 1.

These following sections present the results of the interviews, focus

group discussions and questionnaires and reflect the accessibility of

grassroots stakeholders to land administration related information and

services through a variety of research methods. These sections firstly

discuss the understandings of local people on land use rights and their

importance to them then present the findings on the barriers and issues

of land related services and the recommendations on the land

administration before analysing the accessibility to land information at

grassroots level.

4. STAKEHOLDER AWARENESS OF LAND USE RIGHTS

4.1 Understandings of Land Use Rights

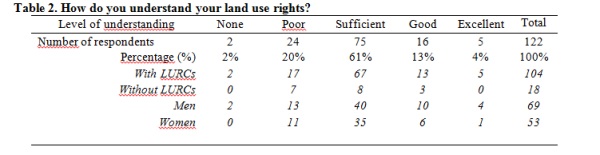

Of the 122 questionnaires responses, 104 individuals and households

(equivalent to 84.6% of participants) had been granted LURCs. This is a

large number in comparison with the average percentage (72%) reported by

provinces to the MONRE (World Bank, 2010) and the figure as of 2013

reported by GDLA. However, only 69 (equivalent to 56.6%) are residential

LURCs.

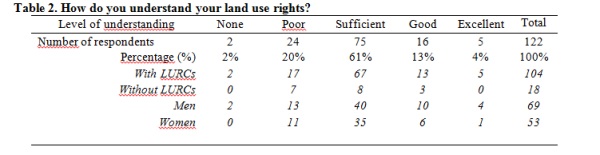

Of the 122 households questioned, 75 (about 61%) indicated that they

sufficiently understand what their land use rights are (Table 2).

However, the majority of participants of the focus group discussions

considered that they are not really good at understanding the land use

rights mentioned in the Law on Land and related legal documents due to

the complicated technical interpretation and understandings.

There was little difference in understanding of land use rights

between men and women in relation to their understanding of their rights

to land (including restrictions and responsibilities) are shown in Table

2. Slightly fewer men (78.26%) stated that their understanding of land

use rights were at the level of competence or higher, compared to women

(79.25%). These results reflected the benefits to women of public

awareness campaigns undertaken under VLAP during the last few years.

Also, the understanding of land users did not differ depending on

whether they had been granted or not granted LURCs.

In the urban area focus group discussions, about 80% of attendees

perceived that they understood their land use rights sufficiently. Some

of them could list the rights of land users set by the law; others could

do this in languages that differentiated terms from the language used in

the legal documents. They could also provide examples for others to

understand and match the ideas. Even though individuals were aware that

they could mortgage their LURCs to access to loans from the commercial

banks, they still were confused about the procedures and the credit

thresholds for borrowing. Although, the majority of attendees were

unaware the value of their land, a few of them had mortgaged their LURCs

for access to credit. In most cases, land users did not understand the

procedures of land valuation. Borrowers simply believed the commercial

banks had applied the right prices set by the government. The

observation and discussion with local people suggested that due to the

limited size of loans and the complicated procedures, many land users,

especially the farmers hesitated contacting the commercial banks to

access credit. Disregarding high interest rates and risks, farmers still

seek “black credits”.

4.2 The Importance of Land Use Rights

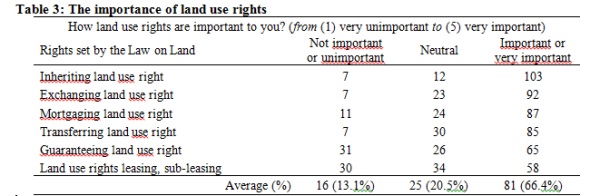

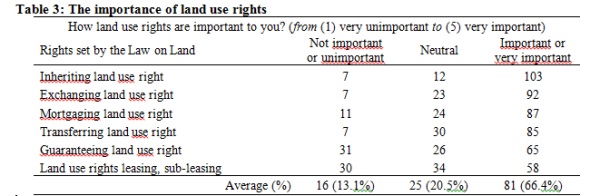

Table 3 presents the results of questionnaire on the importance of

land use rights. Participants were asked to score the relative

importance to them of six property rights related to their land use

rights – as given by the Land Law 2003 (Vietnam National Assembly,

2003).

Overall, 81 respondents (66.4%) indicated that the land use rights

are important or very important, whilst only 13.1% of respondents

addressing that the land use rights are either very unimportant or

unimportant. The rest 20.5% of respondents perceived that the land use

rights are neutral (neither important nor unimportant) to them.

Within the six fundamental property rights of land users listed

above, inheritance of the land use right was evaluated as the most

important right by over 103 (84.4%) participants. The next most

important was the exchange of land use right by 92 (75.4%) respondents.

Additionally, the field observation suggested that the exchange of land

use right supports land users, particularly farmers, to exchange land

use for expanding the farming investments.

Both guaranteeing land use right, and leasing or sub-leasing of land

use rights, were at the bottom of the table of property rights with an

average of just over 50% of respondents suggested they were important.

In general, the results are relatively consistent with the output of

focus group discussions at the three communes. Despite the differences

of locations, communities, and participants’ backgrounds, the majority

of respondents recognised the significant importance of land use rights

to them. The results of focus group discussions could be summarised as

follows:

- Inheritance of land use rights was important to grassroots

individuals and households since all twenty-seven respondents stated

that the inheritance of land use right is an essential right to land

users;

- Mortgage and exchange of land use rights is of great

significance to local land users. The majority of respondents (72%)

in the focus group discussion commented that the mortgage of land

use right was a basic important right despite only few of them

having accessed credit by through mortgaging their land use right.

More than half of the respondents (56%) in peri-urban and rural

areas indicated that exchanging the land use right encouraged them

to use larger land parcels for farming developments;

- One respondent shared their experience of using lease or

sub-lease of land use rights. No respondent mentioned that

guaranteeing the land use right would bring benefits to them.

Nevertheless, there was misunderstanding about the two terms

‘guaranteeing’ and ‘mortgaging’ the land use right, which was

identified when the participants discussed the ease of accessing

credit by using LURCs.

In summary, the above results have shown the importance of land use

rights as well as the benefits of issuing land use rights certificates

to land users. However, a small number of land users successfully

accessed credit by mortgaging the land use right. Land users, especially

in rural areas were still unwilling to, or faced difficulty in, dealing

with commercial banks for loans.

5. Accessibility to Land Administration Services

5.1 Barriers to Land Registration Service Participation

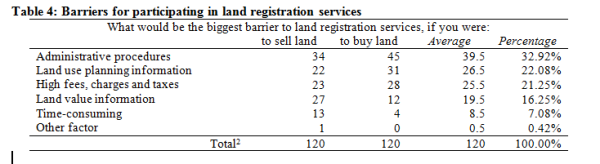

This section presents and discusses the experiences of land users

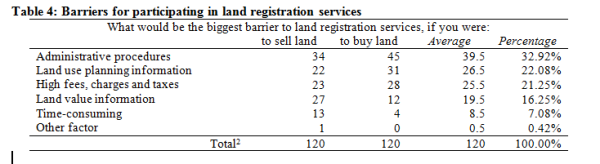

participating in land registration services. The results are presented

in Table 4.

[2] There were 120 participants answering these two questions.

Approximately one-third (32.92%) of respondents indicated that

administrative procedures were the largest barrier for them to do land

registration. The next largest barrier was considered to be limitations

in land use planning information with an average of 22.08% of

respondents. However, there was a difference in the responses for

selling and buying land. While 22.13% of sellers revealed the

limitations in land value information being the second largest factor;

25.41% of buyers acknowledged the difficulty in accessing land use

planning, which relates to land use purpose, land recovery and

acquisition, and land compensation being the second impact for them to

decide.

Time taken to process the service was not considered as a barrier for

the majority of sellers and buyers. Of the responses, just thirteen

sellers and four buyers stated that time-consumption was the factor in

completion of land registration. These figure made an average of 7.08%

of responses.

Generally, the above statistics are consistent with the outputs of

focus group discussions. However, there were some differences between

rural and urban communities. Attendees living in urban and peri-urban

areas were most concerned about the limitation of land use planning

information, citizens living in rural areas were more worried about the

fees, charges and taxes. There were 34 comments from participants

regarding the barriers on land registration services at the focus group

discussions. The results were summarised and could be categorized into

two groups of provision of land information and land policy practices at

grassroots level:

- More than two-third of respondents (73.33%) stated that

the limitation and lack of land use planning information and

documents affected their decisions for transferring land and

involving land registration services;

- The land-related fees, charges and taxes were of concern to the

attendees at the rural area focus group discussions. All respondents

indicated these fees, charges and taxes were still particularly high

and became the biggest barrier (57% of responses from rural area

focus group discussions in particular, or 26.47% of responses from

all three meetings overall). Financial reasons were also mentioned

by 19% and 18% of respondents at urban area, and peri-urban area

focus group discussions, respectively;

- One-third of respondents mentioned the difficulty of

accessing land value information for related land transactions,

including selling, buying and mortgaging. Those people considered

that this limitation was the most difficult for them to sell and buy

land at the best prices. This difficulty was mentioned by14.71% of

respondents;

- There was a similar response regarding land related

administrative procedures at the focus group discussions. Overall,

17.65% of responses stating that the administrative issues were

significant reasons preventing them from participation in land

registration process. The figures were similar at the three

meetings, all between 17-20% of responses.

- At the focus group

discussions, only one respondent mentioned time consumption in land

administration services as a big issue. However, some other

attendees agreed that the land registration services took longer

time than the regulation, especially in applying for LURCs.

Limitations exist in the dissemination of land use planning

information as people interviewed perceived that they had to directly or

indirectly contact cadastral officers to access land use planning

information.

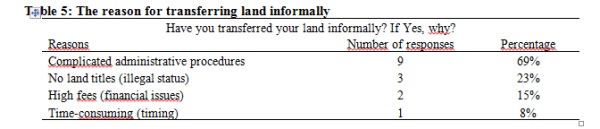

Transferring land informally:

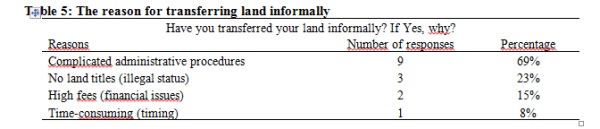

Approximately 12% of participants indicated that they had informally

transferred land over three communes. Due to the only small number of

respondents, the results are not conclusive. However, they provide some

indications of the factors in informal land transactions. The reasons

varied and came from financial issues, administrative procedures,

timing, and legal status.

Of the participants who had transferred land informally, 69% stated

that the complicated administrative procedures as the main barrier,

while legal situation was the reason not doing registration of the 23%.

According to the Land Law, land users could only transfer land

officially providing that the land parcels have been issued LURCs

(Vietnam National Assembly, 2003). Time consumption was not accounted as

an issue to people as only one respondent accounted this as a reason

(Table 5).

There was also discussion on transferring rural land informally in

focus group discussions and it was suggested that if the land users

occupy and use land over a period of time, especially for agricultural

production in areas without new land planning projects, they do not

really need LURCs.

5.2 Support provided by Local Land Administration Authorities

Individuals and households were asked to evaluate the support of

local land administration authorities in specific land related services

and activities, included exchanging, transferring, inheriting,

mortgaging, leasing, sub-leasing, and guaranteeing land use rights, and

two common activities, applying for LURCs and land subdivisions.

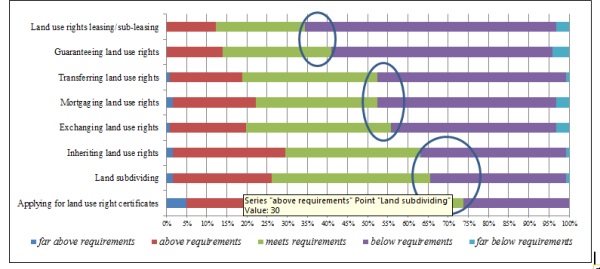

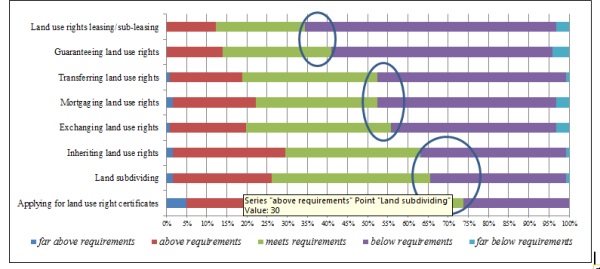

Figure 3: The evaluation of support of

government authorities and staff

Figure 3 describes the comparison of the satisfaction of land users

to the support of local land authorities and officers in different

services and activities. Overall, 55% of respondents were satisfied with

land administration services and activities. People evaluated highly

(74% and 66% acceptable) the support of local staff for applying for

LURCs and land subdivisions. . While the LURCs application activities

establish the initial legal framework to implement other rights under

land related services, the subdivisions of land parcels occur more often

in the rural and peri-urban areas due to the expansions of families and

urbanization process.

These results could be categorised into three groups. The most common

services and activities (an average of 67.5%) including inheritance of

land use rights (63%), subdivision of land parcels, and application for

LURCs received the significant support from local authorities and staff

(74%). The less common services (an average of 53.5%), including

transfer, exchange, and mortgage land use rights received the acceptable

support of local government offices such as land registration offices,

cadastral officers, and financial institutions, as well as heads of

villages, ranging between 52% and 56%. The service relating to less

common processes (an average of 37.7%), including guarantee by land use

right and lease, sub-lease of land use right, received the lowest

support of government agencies, with about 30% to 40% of respondents

satisfied.

On the other hand, there were 45% of respondents dissatisfied with

the delivery of land related services of local related authorities and

officers. Many evaluated the support of the local related staff and

authorities being below requirements (43%), and even far below their

requirements by the rest 2%.

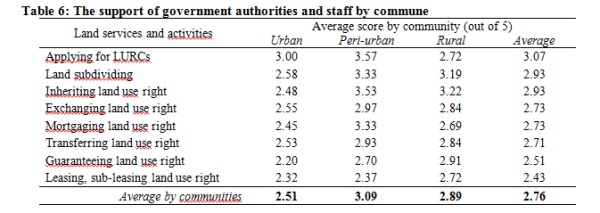

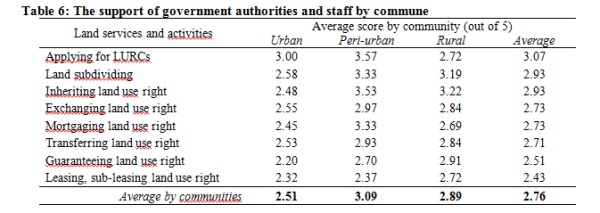

The results of questions on the quality of support provided by local

government authorities and staff were categorised by commune as shown in

Table 6. The scores were computed based on the participants’ responses

under a Likert scale ranging from ‘very poor’ to ‘very good’. Each

choice is given a numerical value and a mean figure for all the

responses is later computed. For example, in this case, a score of 1

relates to ’very poor’, 2 means ’poor’, 3 means ’fair’, 4 means ’good’,

and 5 means ’very good’ in support of government authorities and staff.

Overall, the support provided by local government authorities and

staff in rural and peri-urban areas were evaluated higher than for the

urban area, except for the process of ‘applying for LURCs’ in the rural

area. ’Applying for LURCs’ received the highest score in both urban

(3.00) and peri-urban (3.57) areas, with the support of government

authorities and staff for this service being evaluated as between fair

and good. On average, this service also received the best evaluation of

stakeholders across all three communities with an average score of 3.07.

The lowest evaluation was for the service ‘guaranteeing land use right

services’ in urban area (2.20) with the service receiving the lowest

score across all communes was ‘support for leasing, sub-leasing land use

right’ (2.43).

These results were confirmed, and the differences partly explained,

in the focus group discussions. In total, there were sixty comments

related to the support of local authorities and government staff from

the attendees. These can be summarised as follows:

- The support of local authorities and government staff was

evaluated highest for activities related to the ‘application for

LURCs’. There had been more than one-third of participants (22 out

of 60, equivalent to 37%) presented and shared experiences on the

support of local authorities and staff regarding the activities for

application for LURCs. Of these, 73% provided positive comments.

This was the largest number of comments on this topic;

- The support for conducting ‘land subdivision’ and ‘inheritance

of land use rights’ were positively evaluated by 18% and 13% of

participants respectively;

- The support for activities on ‘lease and sub-lease of land use

rights’ received just only one comment. This suggested that the

activities on leasing and subleasing land use rights at local level

were considered straightforward.

The urban focus group discussions confirmed that the support of

government authorities and staff for ‘applying for LURCs’ was the

highest. The three focus group discussions also confirmed that the

lowest level of support was considered to be for the sub-leasing service

being consistent with the result presented in Table 3.

6. ACCESSIBILITY TO LAND INFORMATION

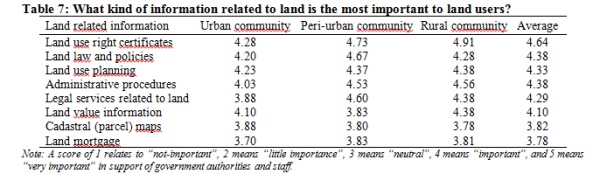

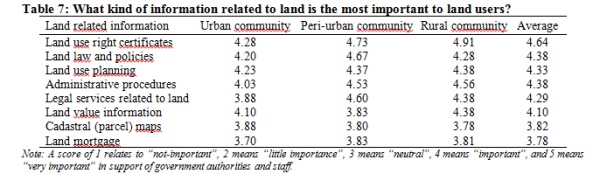

6.1 The Importance of Land Information

Of 122 participants, 96% indicated that land-related information is

important to them. Of these 73% stated that the land related information

is essential in all aspects, including legal and policy information,

technical information, and administrative procedure information.

The information about LURCs was evaluated as the most important to

the land users, especially in rural and peri-urban areas with the scores

of 4.91 and 4.73 respectively (between ‘important’ and ‘very

important’). Information about LURCs includes land titling

implementation plans, administrative procedures, documents, and

supporting documents needed for applying for LURCs. On the other hand,

cadastral maps and sketches and information on land mortgage were

evaluated at the lowest levels of importance to land users with the

scores of 3.82 and 3.78 , respectively – between ‘neutral’ and

‘important’ (Table 7).

The related topics were discussed in all three focus group

discussions which found that these results reflected partly the demands

and understandings of local individuals and households on land

information. Participants, especially for those who living in rural and

peri-urban areas expressed the importance of land value information and

land use planning. The discussion suggested that more than half of

responses at the rural focus group discussion and about 70% of responses

at the peri-urban focus group discussion considered this information

most important to them for making decisions on land use. Participants

also considered that access to land plans, including land use planning

was difficult. Land value information is published under an

administrative decision of a committee without representing this

information on valuation maps. This lacks transparency and makes it hard

for citizens to access information on land values.

A minority of participants required cadastral maps and sketches as

well as land mortgage information. People living in areas covered by the

VLAP were provided technical land parcel sketches by surveyors during

the surveying period for verifying information related such as names,

boundary lengths, and parcel dimensions. They were asked to provide

feedback on the results of surveying for revision, and most focused on

land boundary marking and adjudication. This is one way the surveyors

and government agencies mobilising people to participate in land data

collection. However, individuals can often only verify information such

as names, addresses, and ID numbers. It is hard to verify the accuracy

of the parcel dimensions and areas. Nevertheless, this is a good process

for correction of data from the local stakeholders.

6.2 Accessibility of Land Information

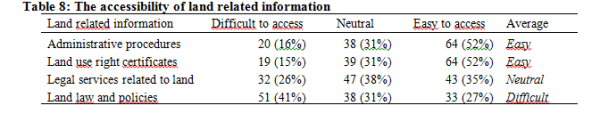

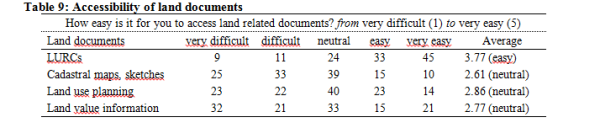

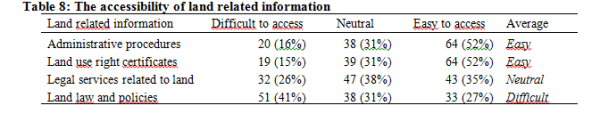

The above section presented the evaluation of land users at

grassroots level on the importance of land information. The results show

that, despite the different responses, individuals and households have

significant demands for land related information. This section presents

the accessibility to land information and land documents by stakeholders

and also discusses the barriers that individuals and household faced (as

shown in Table 8).

Access to land-related ‘administrative procedures’ and ‘LURCs’ were

easier than the other types of information. Over half of participants

(52%) acknowledged it was easy to access these two basic types of

information related to land. On the other hand, people at grassroots

level faced difficulty accessing information on ‘land law and policies’.

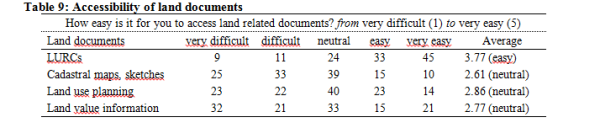

The results in Table 9 show that respondents found the ‘LURCs’ the

most accessible while the other documents are neither easy nor difficult

to access.

The result was confirmed by the outputs of focus group discussion

meetings based on the responses to the question about the difficulties

people experienced when participating in the government land

registration process. According to the discussion, about half of

attendees agreed that the best way to access land related information

for them was to approach the local authority officers. Some attendees

stated that they could access information by visiting public display

sites of local offices. The information they could find included the

list of qualified and disqualified applications for LURCs; information

on land fees and tax; information on compensation, support and

re-settlement plans (in some specific projects containing land

recovery).

Participants were also asked about the accessibility of land

documents including: LURCs, cadastral maps and parcel sketches, land use

planning maps and documents, and land valuation information. The result

shows that the accessibility to LURCs was evaluated as the easiest. This

is consistent with the results in Table 9.

Surprisingly, access to ‘cadastral maps and parcel sketches’ and

‘land use planning information’ were more difficult to access despite

the related legislation listing these as mandatory information needed to

be publicity accessed by stakeholders (Vietnam National Assembly, 2003).

At the focus group discussions, almost all participants revealed that

it was easy to find information about the LURCs. However, the

information about the ‘land use planning’ and the ‘legal dimensions’

(through the maps) of land parcels was hard to access. Some participants

advised that they found it difficult to get enough land use planning

information and documents when they want to buy more land.

Access to information and documents is an important indicator for

reducing rural poverty in developing countries (Binswanger-Mkhize,

Bourguignon, & Brink, 2009). Experiences from grassroots levels show

that the land disputes are often about land boundaries, and disputes can

be reduced through the cadastral survey, mapping and adjudication

process with the participation of land users and providing a clear

mechanism for accessing land related information and documents.

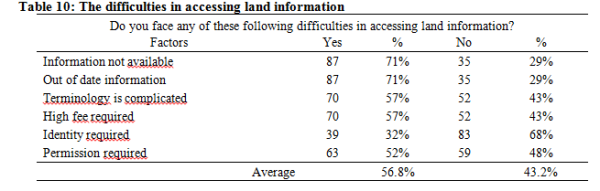

Limitations for accessing land information

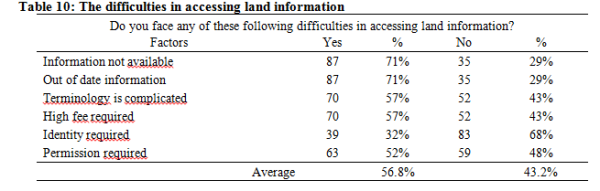

An average of57% of participants indicated that they faced difficulty

in accessing land related information, mostly because of the information

was unavailable or out of date (both 71%). Complicated terminology and

high fee rates for accessing information were also barriers with 57% of

participants (Table 10).

Even though the communal offices are responsible to make information

publicity available, landholders still face difficulty in all of aspects

of accessing land information: quality (out of date, complicated

terminology), quantity (not available), timing (out of date, not

available) and financial (high fees) manners.

The manual methods required to access land information and documents

and the roles of individuals have reduced the level of accessibility of

citizens to land information. This is one of the aims in the development

of an SDI Land proposed under the current research.

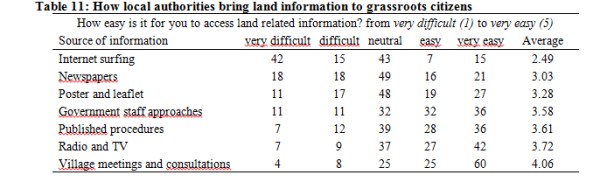

Dissemination of land information at grassroots level

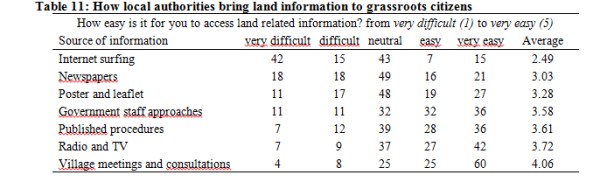

There was uneven result among the methods of providing information

for citizens, including mass media such as television, radio, and

newspapers (both print and online versions) to local measurement

including village meetings, poster and leaflet. Table 11 compared the

evaluation of individuals on the effectiveness of the dissemination of

land information to citizens.

Surprisingly, the most difficult way to access land information was

through the Internet. Approximately half (47%) of the participants

indicated that it was hard to access land information by searching on

the Internet. Only 18% responded that they could easily do this via the

high-tech and speedy search engines. The figure again reflected the weak

dissemination of information about laws and regulations over the

Internet. According to the Law on Land, Law on Urban Planning, the

publication of information on land, such as urban planning (both draft

and approval ones) needed to be made mandatory on the Internet through

the websites of provincial people’s committees or relevant

organisations. This result consisted with the data showed in Table 10

with 71% of participants stating that out of date or unavailable

information made them unable to access suitable land information.

The focus group discussions also supported these figures and

information. The consultations suggested that the information which

people tried to search on the related websites through the popular

search engines include:

- Land related administrative procedures for applying for LURCs,

mortgaging LURCs for loans from commercial banks, selling or buying

land;

- Planning, land-use plans, urban planning both

maps and descriptions;

- Information about land recovery, compensation, and

resettlement, especially when a new plan is approved;

- Information on land leasing, renting and selling;

- Information on charges, fees and taxes related to land including

charges and fees for applying for LURCs, extracting cadastral maps,

extracting legal status of land parcels, land mortgaging, land

subdivisions.

In contrast, local village meetings were still the most effective

channel for people to find and seek information (4.06 – between ‘easy

and ‘very easy’), especially on land use planning and LURCs. The field

observations suggested that, similar to the other traditional villages

in the country, the heads of villages in the case study areas often

organised meetings (officially or unofficially), usually at nighttime to

gather villagers for the dissemination of information. In these

meetings, the villagers are provided with general information such as

land use planning, new project implementation plans, and land taxation

apart from the other information on the agricultural schedules.

7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The above sections described the results of consultation with

grassroots stakeholders on their understanding of land administration

and their accessibility to land related information. The key findings of

these consultations can be summarized to include:

Firstly, the analysis shows that land use rights are significant to

grassroots stakeholders, both those with or without LURCs, and for both

male and female. The issuance of LURCs establishes the legal framework

to protect land tenure of the stakeholder at the highest level. LURCs

provide the legitimate and formal right to access to land.

Secondly, there is a significant demand from grassroots stakeholders

for land related information, in both spatial and attribute data

formats. The analysis suggests that the land information plays an

important role for landholders to make decisions. However, the

accessibility to land information still remains weak, especially for

spatial data (mapping), land use planning, and land value information.

According to the Land Law, information regarding administrative

procedures for land use certificates, cadastral maps, land use planning

and land value is mandatory published in a number of ways and forms for

citizens to access openly and freely. The land administration system

should ensure the information is available and updated with an

appropriate infrastructure for provision of information.

The analysis suggests limitations in land administration processes

have placed barriers to accessing land information. The reasons include

the unavailability of information, out of date information, complicated

terminology, high fee levels, and permission requests. In addition, the

use of the Internet to delivery land information has been ineffective

which suggests that and further development of SDI must recognize the

important role of the traditional village level sharing of information

in a variety of forms. However, the younger people will increasingly

look to the Internet for land information. By 2013, there had been more

than 31 million Internet users in Vietnam (MIC, 2013). The huge number

has been still rapidly increasing over the last few years and predicted

to be doubled in 2016. The figure shows the potential of information

provision on Internet is huge as websites can offer quick access to

information for stakeholders simply with a connection. On the other

hand, the related laws and regulations have already outlined the types

of information that must be published online or not online. In fact,

despite the rapid increase of number of the Internet subscribers in the

country, the usage of this technology for dissemination of land related

information has been still limited. Investment in an efficient

infrastructure such as a land portal would make the accessibility to

land information available and easy.

Thirdly, local government land authorities and staff should

be provided with ongoing training under ongoing capacity building

programs. In order to improve accessibility of government land

information to citizens, this should include customer service training

and improvements in efficiency. The benefit to the State is that this

may reduce the percentage of people who transfer land under informal

land markets, bringing them into the formal economy.

Lastly, public awareness rising campaigns should be

implemented more often to local stakeholders. Initially, individuals and

households need awareness of the importance of LURCs to ensure their

land tenure security. Land users should also be informed their rights,

restrictions and responsibilities fully to avoid social risks of

implementation of land use rights. For instance, participation in LURCs

process and land registration will reduce land disputes and complaints

which often happen at grassroots level. Traditional village level forums

continue to be important for awareness raising. At the higher level,

land users should be guided to seek and request land information they

need by using one-stop shop and the Internet via a land portal.

The paper describes the results of stakeholder consultations on

accessibility to land administration in case study areas. Participants

living in the study areas perceive that LURCs and related services are

the most important to protect their rights on land and understand their

land use rights competently. The demands of access to land, land

information, and land documents have been recently increasing. However,

the level of accessibility to land information still remains low. There

has existed an inefficient link among government agencies for accessing

and sharing data efficiently and effectively.

The results have included evaluations of limitations, and barriers

which could support to improve the land administration system, reform

land administrative procedures, raise awareness for local citizens, and

building capacity for government staff.

REFERENCES

Binswanger-Mkhize, H. P., Bourguignon, C., & Brink, R. v. d. (2009).

Agricultural Land Redistribution: Toward Greater Consensus: The World

Bank.

DEPOCEN, World Bank, UKAID, & VTP. (2014). Land Transparency Study:

Synthesis Report. Hanoi, Vietnam.

Embassy of Denmark, Embassy of Sweden,

& World Bank. (2011). Recognizing and Reducing Corruption Risks in Land

Management in Vietnam (Reference book). Hanoi, Vietnam: National

Political Publishing House.

FAO. (2012). Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of

Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food

Security. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Malesky, E., Tuan, D. A., Thach, P. N., Ha, L. T., Lan, N. N., & Ha,

N. L. (2015). The 2014 Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index:

Measuring Economic Governance for Business Development. Hanoi, Vietnam:

Labour Publishing House.

Martini, M. (2012). Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in

Vietnam. U4 Expert Answer, 315.

Maxwell, D., & Wiebe, K. (1999). Land Tenure and Food Security:

Exploring Dynamic Linkages. Development and Change, 30(4), 825-849. doi:

10.1111/1467-7660.00139

MIC. (2013). Vietnam White Book on Information, Comminication and

Technology 2013. Hanoi, Vietnam: Information and Communication Punishing

House.

Muggenhuber, G. (2003). Spatial Information for Sustainable Resource

Management. International Federation of Surveyors: Article of the Month,

September 2003.

Quizon, A. B. (2013) Land Governance in Asia: Understanding the

debates on land tenure rights and land reforms in the Asian context.

Vol. 3. Land Governance in the 21st Century: framing the debate series.

Rome, Italy: The International Land Coalition.

Steudler, D., & Rajabifard, A. (Eds.). (2012). Spatially Enabled

Society. Copenhagen, Denmark: International Federation of Surveyors

(FIG).

Thu, T. T., & Perera, R. (2011). Consequences of the two-price system

for land in the land and housing market in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Habitat International, 35(1), 30-39. doi:

10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.03.005

Vietnam National Assembly. (2003). Law on Land 2003. Hanoi, Vietnam.

Vietnam National Assembly. (2013a). The 2013 Consitution of the

Socialist Republic of Vietnam (adopted by National Assembly Term XXII at

its sixth Session on November 28, 2013). Hanoi, Vietnam.

Vietnam National Assembly. (2013b). Law on Land 2013. Hanoi, Vietnam.

Widman, M. (2014). Land Tenure Insecurity and Formalizing Land Rights

in Madagascar: A Gender Perspective on the Certification Program.

Feminist Economics, 20(1), 130-154. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2013.873136

World Bank. (2009). Vietnam Development Report 2010 - Modern

Institutions. Hanoi, Vietnam: Joint Donor Report to the Vietnam

Consultative Group Meeting (December 3-4, 2009).

World Bank. (2009). Vietnam Development Report 2010 - Modern

Institutions. Hanoi, Vietnam: Joint Donor Report to the Vietnam

Consultative Group Meeting (December 3-4, 2009).

World Bank. (2011). Report of the Study on National Spatial Data

Infrastructure Development Strategy for Vietnam. Hanoi: WB Joint Working

Group of the World Bank and Ministry of Natural Resources and

Environment.

World Bank, & Government Inspectorate of Vietnam. (2013). Corruption

from the Perspective of Citizens, Firms, and Public Officials - Results

of Sociological Surveys. Hanoi, Vietnam: National Political Publishing

House.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Mau Duc Ngo commenced his PhD study on SDI for land administration at

the School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences of RMIT University in

July 2012 as an Australia Development Scholarship (ADS) awardee. The

research investigates the development of SDI and aims to develop and

implement an SDI model for land sector in Vietnam to enable data

updating and sharing as well as access to land information by all

stakeholders. Mau has been working for the General Department of Land

Administration (Vietnam) since 2001. He holds a BSc in Land

Administration and a MEng in Urban Planning and Management.

David Mitchell is an Associate Professor at RMIT and a licensed

cadastral surveyor. He has a PhD in land administration. David is

co-chair of the GLTN Research and Training Cluster, and member of the

GLTN International Advisory Board. At RMIT University he teaches

cadastral surveying and land development and undertakes research

focusing on the development of effective land policy and land

administration tools to support tenure security, improved access to land

and pro-poor rural development. He also has a strong research focus on

land tenure, climate change and natural disasters.

Donald Grant was the New Zealand Surveyor General until February 2014

when he took up the position of Associate Professor in Geospatial

Science at RMIT University. He holds a BSc Honours in Physics from

Canterbury University, a Diploma in Surveying from Otago University and

a PhD in Surveying from the University of New South Wales. He registered

as a surveyor in 1979 and is currently registered as a Licensed

Cadastral Surveyor in Victoria.

Nicholas Chrisman was Head of Geospatial Disciplines at RMIT

University until December 2014. He is a Professor and holds a PhD in

Geography with more than forty years teaching experience at university

level. Currently, he is an editor for Journal of Cartography and

GIScience, published by Taylor & Francis. Nicholas has published two

books and over a hundred scientific articles. He is a member of Panel on

Developing Science, Technology, and Innovation Indicators for the

Future, National Research Council (USA).

CONTACTS

Mau Duc NGO

School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences

RMIT University

GPO Box 2476

Melbourne, Victoria 3001

Australia

Tel. +61 3 9925 1132 / Fax +61 3 9925 2454

Email: [email protected] @mauducngo

Web site: http://www.rmit.edu.au/mathsgeo

|