Land Access and Community Entry Challenges in Environmental Surveys Selected cases from NigeriaIyenemi Ibimina KAKULU, Simeon IGBARA,

|

|

|

![]() This article in .pdf-format (14 pages)

This article in .pdf-format (14 pages)

1) This paper is a Nigerian Peer Review paper, which will be presented at FIG Working Week 2013 -6-10 May, in Abuja, Nigeria. We are pleased to share this Peer Review paper with you already now prior the conference to highlight one of the challenges that Nigerian surveyors are dealing with, namely land access restrictions. Together with UNEP, the authors have undertaken a comprehensive environmental survey of several communities in the Niger Delta region, and their findings and methods are interesting not only in Nigeria but can be used in countries all over the world. At the conference you will be presented to many further papers both from Nigeria, Africa, and Internationally, that highlight the current challenges for surveyors.

Key words: Environmental surveys, land access, community entry

Environmental surveys that require access to communal, family and individual farmlands, mangrove swamps or fishing villages to obtain data, can be very challenging to any team of environmental professionals working locally or on international development related projects. Land access restrictions may be imposed by different interest groups or stakeholders whose actions could interfere with the overall conduct or success of any environmental survey irrespective of its laudable goals and objectives. It might also be that the traditional land tenure patterns may differ significantly from land tenure patterns as understood by a multicultural project management team. In Nigeria, following a Federal Government invitation in 2006, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) undertook a comprehensive environmental survey of several communities in the Niger Delta region following reported and documented high levels of hydro-carbon pollution in these areas . Using an innovative and culture-based community entry and land access strategy developed by the UNEP project management team in a collaborative partnership with the Rivers State University of Science and Technology (RSUST), this paper presents the key considerations in this innovation and highlights the challenges encountered in the practical implementation of several key stages of the land access strategy . It documents real-life challenges as they were experienced in the field and which serves as feedback to the process and produces refinement and adaptation options for replication in similar environmental studies.

Environmental surveys can range from very simple projects involving

the investigation of a single site to large and more complex projects

involving multiple locations and investigating multiple environmental

media. In very simple description, an environmental assessment project

will involve a preliminary historical and literature review on the study

area, minor or major fieldwork and sampling followed by laboratory

analysis and report production. Being in the nature of a project with

set objectives, it is expected that the fundamental project management

principles and procedures will apply and that predetermined goals and

targets will be met. Land is an asset of enormous importance for

billions of rural dwellers in the developing world, and especially in

ACP countries where land is not just an economic asset, but has strong

political, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions (Boto, Peccerella,

& Brasesco, 2012, p. 5).

However, in real life situations as in the case of the UNEP Ogoniland

project, a combination of traditional and innovative project management

strategies had to be used in order to achieve overall success of the

project. One of such innovations amongst several others was the use of a

culture-based land access strategy. UNEP acknowledges that the two year

study of the environment and public health impacts of oil contamination

in Ogoniland is one of the most complex on-the-ground assessments ever

undertaken by UNEP. (UNEP, 2011, p. 8) This assertion is quite

significant judging by published statistics on the number of community

and town-hall meetings that were held throughout the life of the

project.

On the issue of land access, the UNEP report acknowledges that,

‘facilitating access to specific sites where UNEP specialists needed to

collect data was a major exercise and one that needed to be handled

delicately as ownership was not always clear with attendant potential

for local conflict. Multiple negotiations were often required, involving

traditional rulers, local youth organizations and individual land owners

or occupiers. A Land Access Team, provided by RSUST, working in

conjunction with UNEP’s Communications Team, managed these challenging

issues, explaining precisely what the UNEP team would be undertaking,

where and at what time. (UNEP, 2011, p. 57)

The RSUST driven Land Access strategy was implemented by a land Access

Team (LAT) made up of academics and student interns drawn from the

departments of Estate Management; Urban and Regional Planning and Land

Surveying in collaboration with Academics from the departments of Estate

Management and Geo-informatics at the Rivers State Polytechnic (RIVPOLY)

in Bori. This innovative strategy went through several iterative phases

and refinement throughout the implementation and review of daily

feedback from the UNEP technical teams in the field. The process however

achieved reasonable success in meeting its set objectives and can be

used or adapted for use in similar development and environmental

assessment projects.

A project is essentially a way of organising people, and a way to

manage tasks. The British Standards definition BS 6079 – 1 defines a

project as a unique set of coordinated activities, with a definite

starting and finishing point, undertaken by an individual or

organization to meet specific objectives within defined schedule, cost

and performance parameters. Project management is simply a style of

coordinating and managing work. What differentiates it from other styles

of management is that it is totally focused on a specific outcome and

when this outcome is achieved, the project ceases to be necessary and

the project is stopped (Newton, 2009, p. 11) Projects can be categorized

by their content, complexity and scale. Complexity can be assessed by

either being risky, novel or intellectually complex. Project management

has been defined severally but in terms of real life applications it

means different things to different people and disciplines. A project

management team is however responsible for determining what is

appropriate for any given project.

The PMBOK Guide (PMI, 2010)definition, meaning and theories of project

management provide a general framework for this review. It defines a

project as a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product,

service or result, and as such has a definite beginning and definite end

(PMI, 2010, p. 4). Achieving a project’s objectives signals the end of a

project unless it has to be terminated. Deliverables are expected at the

end of each project or sub-project components of a main project. These

would usually be in the form of products, services or results usually

documented. It generally assumes a structured approach to projects but

in the case where an unstructured or adaptive approach succeeds, then

capturing the methodology which led to this success makes it adaptable

for replication. The aims and objectives of this paper are to present

details of the novel approach utilized in the Ogoniland study in the

area of land access and community entry in a technical collaboration

between UNEP and the Rivers State University of Science and Technology

(RSUST), Nigeria.

Project management may be defined as the investment of capital in a time

bound intervention to create productive assets and the energy and

inventiveness of people, plays an important role in projects and that

this role is just as important as the expenditure of physical and

financial resources (Cussworth & Franks, 1993). Projects vary in type

and size and the cycles may also differ. The general idea however is

that a project goes through several stages and phases from

implementation to and subsequently evaluation. The assumption might be

that this is a linear relationship but in real life experiences, it is

much more complex. Acyclic pattern of projects is more popular. In

social sciences related projects that deal with human capital, a more

adaptive strategy is advocated.

Project management involves the application of knowledge, skills, tools

and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements (PMI,

2010, p. 8). It is a broad field but one of the significant requirements

of a project management team is the ability to adapt their approach to

the different concerns of various stakeholders. Projects do not take

place in a vacuum but are implemented in a web of social, cultural,

economic and other contexts. An understanding of the nature of a

particular project will enable a reader appreciate the project

management challenges involved therein.

The UNEP Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland Project was

commissioned by the Federal Government of Nigeria in 2006. The main

purpose of the project was to assess the extent of oil pollution in

Ogoniland following the failure of decades of negotiation, initiatives

and protests to deliver a solution to oil production related unrest and

crises in parts of the Niger Delta. The geographical description of

Ogoniland as per the UNEP study, covers four Local Government Areas

(LGAs) of Rivers State in Nigeria which include Khana LGA, Tai LGA,

Gokana LGA and Eleme LGA.

There are several ways to manage a project in order to achieve the

desired objectives of the specific project but this cannot be

accomplished without taking the project environment into consideration.

The complexity, risk, size and resources including other socio-cultural

or socio-economic considerations, will determine the final approach. The

UNEP led Ogoniland project can best be described as a complex project

considering the fact that it was risky, novel and intellectually complex

and is a classic example of a project in which an adaptive strategy was

applied throughout its duration working in an environment filled with

suspicion and distrust and trying at the same time to win the confidence

of the people to enable the project proceed.

Essentially, the focus of any environmental assessment project is to

collect relevant data, analyse it and produce a report on the findings

therefrom. Such a simple description however does not match the

complexity of the process as evidenced in actual field operations. As

with other projects, the socio-cultural environment in which a project

takes place presents its own challenges to a project management team and

an understanding of the expectations of local community is essential.

Several authors within the fields of project management advocate some

for standardization, technique and procedures and while this is a

laudable desire, the real world out there presents a changing world and

the demands of project management become more of a subjective rather

than a deterministic process. A project management process might succeed

with a reasonable amount of latitude that allows flexibility and

innovative particularly when working in developing countries. Decision

making may then be based on what is feasible and achievable within a

given scenario as against pre-determined models or a combination of

both.

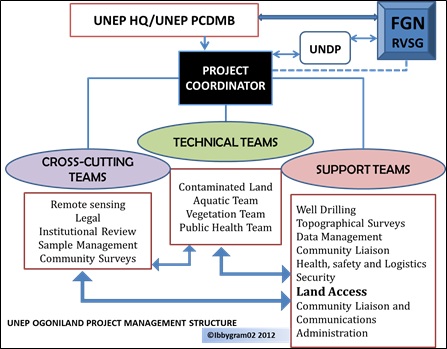

There are several issues to consider in any project or in sub-projects of a main project. These include the methodology; implementation of the project management process; the project management culture and organizational structure; estimating; planning and scheduling, project execution; control and conflict management. In the case of sub-projects on the Ogoniland study, the larger project was subdivided into manageable units and single activities on the project where undertaken by project sub-teams along their thematic area or subcontracted out. The UNEP study project management function was executed by three major teams managed by an international project coordinator and overseen by UNEP Post Conflict and Disaster Management branch (PCDMB in Geneva and UNEP headquarters, in Nairobi. It is important to recognize the fact that different players in a project management team may want a methodology that is designed for their particular benefit and conflict may often arise between parties which need to be sorted out over the life of the project in order to deliver an end product, this project was not an excepting but through a series of meetings and project briefings, conflict issues were very easily resolved. The main structure as detailed in Fig. 1 is outlined below.

Figure 1 - UNEP Ogoniland Project Management Structure (Adapted from

(UNEP, 2011, pp. 54-58))

The effective coordination of a mega project of this nature was impossible to accomplish without the technical, cross-cutting or support teams to achieve the project goals and objectives. This paper focuses on the activities of the RSUST/RIVPOLY driven Land Access Teams and challenges associated with their task and makes recommendation for replication in similar projects.

A social and organizational theory framework underlies this study.

The methodology uses an illustrative case study combined with field

research data collection techniques and provides detailed description of

the design and implementation of an innovative community entry and land

access strategy developed by the UNEP project management team in

collaboration with RSUST and executed jointly between RSUST and RIVPOLY

in conjunction with the UNEP team.

The choice of field research as a methodology is because it involves a

range of well-defined, although variable, qualitative methods listed as

follows:

Although the field research methodology is generally described as qualitative research, it often includes quantitative dimensions. This study presents a descriptive account of land access activities undertaken during the Ogoniland project as primary data source, analyses it and presents a rich picture of the EIA project management process. Data collection was by participant observation and the examination of field records and analysis of documents produced within the group of land access personnel. The authors were participants on the project and as such participant observation methodology was considered suitable and was utilized to give a first-hand participant account of the project as it occurred. Through a process of self-analysis and project review, the findings are outlined. The advantage of this approach is that it presents a rich picture of actual process by using content analysis techniques on the daily field activity log and content analysis of the LAT daily records of field activities.

Land Access Challenges on the Ogoniland Project

At the commencement of the environmental assessment project, the tool

available for accessing and inspecting impacted areas was a map showing

areas with oil infrastructure and records of historical spills within

the proposed study area. Very few community names were associated with

these locations and a major challenge immediately identified, was how to

access each impacted location without appearing to be trespassing,

actually trespassing or carrying out activities that could instigate

additional conflict in the area considering that the entire project had

conflict resolution as its underlying goal. Considering that all sample

collection activities involved land access to specific locations or

across specific locations to nearby creeks or rivers, a robust land and

transparent access strategy was required which would in the absence of

available records of land ownership in the area. Land ownership

verification required knowledge of the local land use patterns and

traditional verification processes.

The initial task in developing a community entry protocol was to obtain

a clearer picture and understanding of the specific tasks that were to

be undertaken by each of the four thematic technical teams and the cross

cutting teams including what data they expected to collect during the

field work, and how? The Land Access Team (LAT) members participated in

the initiation and development of a community entry protocol that was

based on an understanding of the traditional land access practices in

Ogoniland. Generally, the Ogoni’s practice the traditional bush-entry

systems where payments are demanded for and expected to be made prior to

entry upon ancestral land. This activity is however be preceded by

meetings with the community chiefs, elders, youth, women and children.

The purpose of such meetings is usually to establish a relationship

following which formal business talks can take place and land entry

authorized with or without any financial payments.

Each step had specific set of objectives and deliverables as shown in

Fig. 2. The horizontal arrows indicate firewalls which consist of

expected deliverables from the preceding step prior to proceeding

further. Although fast tracking did occur it was based on first of all

having assessed the potential risk in skipping any step.

Figure 2 – Community Entry protocol – UNEP Ogoniland Project

If it was not possible to actualise the deliverables from a preceding step, the process terminated at this point or was repeated before progressing to the next phase. The four (4) distinct phases are discussed further. Towards the later part of the project, a special reconnaissance protocol was developed for use in areas when the community had already been sensitized and there was no need for step 1 and the process commenced in steps 2 – 4, see Fig 2.

Figure 3 - Abridged Land entry protocol

The main purpose of the pre-entry reconnaissance step was an initial

attempt to gain vehicular access to locations within close proximity of

the impacted grids on the map of historical spills and to identify the

Local Government Area (LGA) within which it falls. It was also to assess

the likely physical access challenges envisaged at the actual

reconnaissance phase. This process was facilitated using GIS tools and

equipment and driven by the Community Liaison Assistants (CLA) Team, the

project Technical Assistants (TA’s) with support from the health/safety

and the security teams. Initial contact was established within the

general geographical location of impacted areas and the surrounding

communities identified. The deliverables from Step 1 included the

identification of communities and the generation of follow-up activities

for the Community Liaison Assistant (CLA) who took over the

responsibility at this point to make actual contact with the community

leaders and arrange a sensitization meeting in the Step 2. This was the

most important outcome of the process and what was used to weigh the

success or failure of a sensitization activity.

The firewalls surrounding this initial step prohibited any physical land

entry at this stage because it is assumed that the more remote villages

would most probably not have been informed about the project. This could

result has resulted in a misconception about the purpose of land entry

and construing this action to mean violation of the traditional

community land entry protocols or outright trespass. The CLA was the

only support team member authorised to physically disembark from the

project vehicle (except for technical reasons such as GPS signal

failure), in order to interact with the locals to confirm the actual

indigenous name of the location, obtain leads to the traditional

leadership structure and possibly a contact person. This activity

provided the basis upon which the CLA conducted follow-up community

based investigation, established firm contacts and negotiated a

community sensitization and stakeholder meeting for the project

management team to be undertaken in Step 2.

A sensitization meeting to formally introduce the project to the community was the main activity in step 2. This activity was CLA driven in conjunction with the LAT. The main purpose of a sensitization meeting was three-fold:

The nomination of community contact persons was the single most important outcome of this step. It indicated acceptance or otherwise and a measure for success or failure at later stages of the project. A step 2 meeting was considered to be inconclusive when contact persons are despite the level of project awareness it raises. The firewalls surrounding this step are hinged on obtaining the names of contact persons who would subsequently work with the project team, as community representatives. Without getting these names, the process could not proceed to the next step as community acceptance was not certain. Exceptions to this rule were where a step 2 meeting was either rescheduled or it was unanimously agreed that the names and contact telephone numbers of such representatives, would be forwarded at a later date to the CLA.

The land access negotiation in step 3 was an important community

based activity during which physical land entry occurs and

owners/occupiers of impacted farmlands are identified as this was

crucial to the future sampling activity and community surveys. The land

access team, made up primarily of land management academics and

professionals resident in and around the study area and armed with local

knowledge of community perceptions and expectations in connection with

land, worked with the UNEP team to develop community entry protocols for

the technical teams, the cross cutting teams as well as the support

teams throughout the life of the project. The land access team (LAT)

coordinated this process and were taken by the community nominated

representatives to visit all known oil spill sites within their area

particularly the historical sites indicated on the UNEP map. These sites

are geo-referenced and the LAT assesses the nature of the terrain, the

immediate and potential accessibility challenges in view of a larger

team visiting the area using project vehicles and carrying equipment in

subsequent phases. Alternative access routes are explored and feedback

was given to the project health, safety and logistic as well as the

security support teams for planning.

The community nominated representatives played a key role in the initial

identification of family lands and actual land owners. Armed with an

understanding of the land holding structure in the area which is by

family, they guided the LAT to the elders, chiefs and family heads of

plots of interest with which the LAT negotiated access. Acceptance

during this level of investigation was measured by the nomination of

persons at the family level to work with the UNEP teams during the

sampling phase as labour hands and as family representatives. All

de-bushing needs were dealt with using local community labour selected

first by the specific family who owned the land and subsequently

approved by the community youth leader(s) and nominated representatives.

Conflict situations did arise occasionally where there were

controversies on the boundaries of specific sites between different

families. The usual approach then was to work with youth from both

families which easily resolved the crisis. Ina situation where crops

were to be removed to create access, appropriate compensation was

estimated, negotiated and paid for. The deliverable from this exercise

was a confirmed date or range of possible dates during which the family

representatives would be present for the reconnaissance activities in

step 4, to take place.

Step 4 involved actual entry for the purpose of work in connection

with drilling of boreholes and /or sample collection on

community/family/individual land. During this activity, the technical

team were physically on the land and were allowed to spend time carrying

out their Reconnaissance activity. The CLA was also present throughout

this activity while the LAT was there to ensure that all required

de-bushing had been done and that the community nominated

representatives were present to guide the TAs in such a way that they

did not unknowingly stray into neighbouring farmlands or communities.

Where this happened on a few occasions, the combined team of LAT and

CLA’s were on the spot to sort out these issues with the agitating

communities. In severe cases of conflict, the CLA took the matter to the

LGA where it was later resolved. Step 4 of the land entry protocol in

any location signalled the beginning of the sampling activity which

commenced with the drilling of ground-water monitoring wells.

There were several challenges during this phase particularly due to the

fact that with certain spills, a community might have taken the TA’s to

the impacted area within their own community boundaries while, the

epicentre might actually have been in a neighbouring community for which

access had not yet been negotiated. Sometimes an on-the- spot decision

to quickly visit and see the epicentre angered those communities as

their permission had not been sought prior to entry. The problem was

usually much more complex in cases where multiple communities laid claim

to a single impacted site. On the whole, LAT delivered all sites for

reconnaissance and kept community members happy by making prompt

payments for their time in the field.

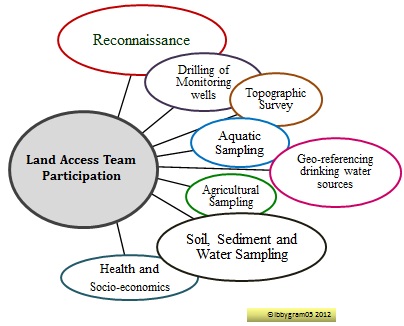

The reconnaissance phase signalled beginning of the sampling phase which was christened MARIO by the project management team. It was named after the one of the Chief Scientific Expert on the project. The Mario phase was packed with non-stop activity up until the end of the project. The land access team participated in all the activities shown See Fig. 4.

The LAT participated in a cross section of project activities and were always in the field to deal with land access requirements or de-bushing to ensure the project team experts from any of the project thematic areas did not experience undue setbacks in the field. They covered all activities from drilling to socio-economics. As mentioned earlier, the CLA’s worked closely with the LAT particularly in identifying the owners. Their activities where fairly structured following a similar pattern developed earlier in the life of the project.

As anticipated, during the initial phases, there were few instances

where team members having not fully understood the essence of the

firewalls between each phase, attempted to enter community land but were

prevented from gaining access and in a few isolated cases, with threats

from the community youth and in others, community names were submitted

to the CLA at a later date. Members of the Land Access Team were present

at over 95% of all Step II activities during the life of the project

occasionally being unable to attend due to conflicting field

assignments. In such cases, LAT depended heavily on feedback from the

CLA’s regarding the nominated representatives. This was extremely

important as the succeeding step depended on their knowledge of the

community representatives.

Where a sensitization activity ended without the appointment of

community representatives, it became impossible to do any further work

in the area. So this was a crucial step and a very traditional land

access protocol for the Ogoni's. In most communities in Eleme and Khana

LGAs, the community representatives were made up of 3 persons, the Chief

Security Officer (CSO) of the community, the youth leader and a

representative of the chief’s palace to give him feedback and progress

reports. In Gokana and Tai Local Government Areas, the number was

usually increased to 5 as they added a representative from the Landlords

of impacted areas with oil infrastructure and members of the Pipeline

Vigilante Contracting teams. The process had to be flexible enough to

allow for these variations as we progressed from LGA to LGA.

This activity involved actual visits through community farm tracks to

the exact location of impacted. Vehicles were used but in a majority of

the cases motorbikes were used or the full team walked long distances to

reach these locations. This process was important in order to determine

(ahead of the UNEP Technical team reconnaissance visit), the nature of

the terrain, vehicular access challenges and the de-bushing requirements

if any, to gain access to specific sites. The actual land owners of

impacted sites were identified as this would be crucial to the success

of the of the reconnaissance phase in terms of land entry and

recruitment of unskilled labourers. cess enabled them understand a

little more about the local terrains, visit with the owners of actual

impacted sites and schedule visit for the project technical team to do

an initial reconnaissance survey. This was a very challenging phase of

the project with several security issues and success depended a lot on

the interpersonal skills of the particular LAT member.

Depending on the expanse of the impacted areas, the process usually

lasted 2 – 3 day on the average. Armed with a GPS, the LAT member could

give more precise feedback to the technical team regarding the actual

physical location of the impacted area relative to the grid on the map,

the motor able distance and alternative access routes, the expectations

of the community members as well. If the area was overgrown and would

make access difficult for the technical team in Step 4, LAT made

arrangement for de-bushing making all necessary payments as appropriate.

During each of these visits, LAT incurred financial expenditure on

preliminary clearing to enable them reach the site, payment for upwards

of 4 motorbikes that took them to the location and a modest remuneration

for the community representatives who worked with them. The deliverable

from this exercise was a firm date for the reconnaissance activities

undertaken by the technical assistants.

It is possible to say that the adaptive project management strategy used in the Environmental assessment of Ogoniland project was responsible for its timely completion and publication of the full report in 2011. The step-by community entry protocol enabled the formation of lasting friendship between community youth and members of the land access teams who gradually become constant figures within the community. By participating in the sensitization meetings in Step 2 and taking responsibility for nominating community contact persons to work with the UNEP team, a sense of ownership of the project and its process was developed by several communities. The process is replicable in similar projects.

al., B. B. (1994-2012).

http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=60. Retrieved

October 17, 2012

Boto, I., Peccerella, C., & Brasesco, F. (2012). Land Access and Rural

Development: new challenges, new opportunities. Brussels.

Cussworth, J. W., & Franks, T. R. (1993). Managing Projects in

Developing Countries. Essex: Addison Wesley Longman Limited.

Gardiner, P. (2005). Project Management: A strategic Planning Approach.

Palgrave.

Harrison, F., & Lock, D. (2004). Advanced Project Management - A

Structured Approach. Aldershot: Gower publishing Company.

Harrop, O. D., & Nixon, A. J. (1999). Environmental Assessment in

Practice. London: Routledge.

John J. Macionis, K. P. (2012). Sociology: A Global Introduction.

Prentice Hall.

Kerzner, H. (2003). Project Management - A Systems Approach to Planning,

Scheduling and Controlling. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.

Kerzner, H. (2003). Project Management Case Studies. New Jersey: John

Wiley and Sons.

Lock, D. (2007). The Essentials of Project Management. Aldershot: Gower

Publishing Limited.

Maylor, H. (2003). Project Management. Harlow: Pearson.

Meredith, J., & Mantel, S. J. (2010). Project Management: A managerial

Approach. Asia: Wiley and Sons.

Modak, P., & Biswas, A. K. (1999). Conducting Environmental Impact

Studies for Developing Countries. Japan, Japan: United Nations

University Press.

Newton, R. (2009). The Project Manager: Mastering the Art of Delivery.

Prentice Hall.

PMI. (2010). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge.

Newtown, USA: PMI.

Reiss, G. (2007). Project Management Demystified. New York, USA: Taylor

and Francis.

UNEP. (2011). Environmental Assessment of Ogoniland. Nairobi: UNEP.

Wikipedia. (2012). Field Research. Retrieved October 25, 2012, from

Wikipedia Free Encyclopedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_research

The support of the School of Real Estate and Planning, Henley Business School, University of Reading, United Kingdom, by way of access to library resources is hereby gratefully acknowledged.

Mrs. Iyenemi Ibimina Kakulu,

Senior Lecturer,

Department of Estate Management,

Rivers State University of Science and Technology,

Nkpolu, Port Harcourt,

Rivers State, Nigeria

[email protected]

Mr. Simeon Igbara,

Lecturer, Department of Estate Management,

Rivers State Polytechnic, Bori,

Rivers State, Nigeria

[email protected]

Mr. Isaac Akuru,

Lecturer, Department of Estate Management,

Rivers State Polytechnic, Bori,

Rivers State, Nigeria

Nekabari Paul Visigah

Department of Urban and Regional Planning

Rivers State University of Science and Technology,

Nkpolu, Port Harcourt,

Rivers State, Nigeria

[email protected]